After years of working with federal and provincial governments across multiple administrations, I have learned something uncomfortable about reform in Pakistan. Failure here is rarely accidental. It is usually defended.

Good ideas do not collapse because they are flawed. They collapse because they threaten rents. Task forces delay decisions. Consultants provide cover. Reports are launched and quietly forgotten.

Agriculture has survived in this stagnant equilibrium because the people who lose from inefficiency are scattered, while the people who benefit are organized. Farmers absorb losses individually. Consumers pay quietly through higher prices. The winners sit at chokepoints such as credit, procurement, imports and subsidies, and they defend the system with discipline.

The numbers are no longer small enough to ignore.

Pakistan loses more than one billion dollars each year to avoidable post harvest waste. It imports three to four billion dollars in edible oils, two to three billion in pulses and more than two billion in cotton annually, all commodities we are capable of producing. Closing even part of these gaps while building processing and logistics capacity would improve our external balance by five to eight billion dollars a year. Over a decade, that compounds toward fifty billion dollars in value we currently lose or import.

This is not hypothetical upside. It is value already grown, already demanded and already wasted.

The waste we have normalized

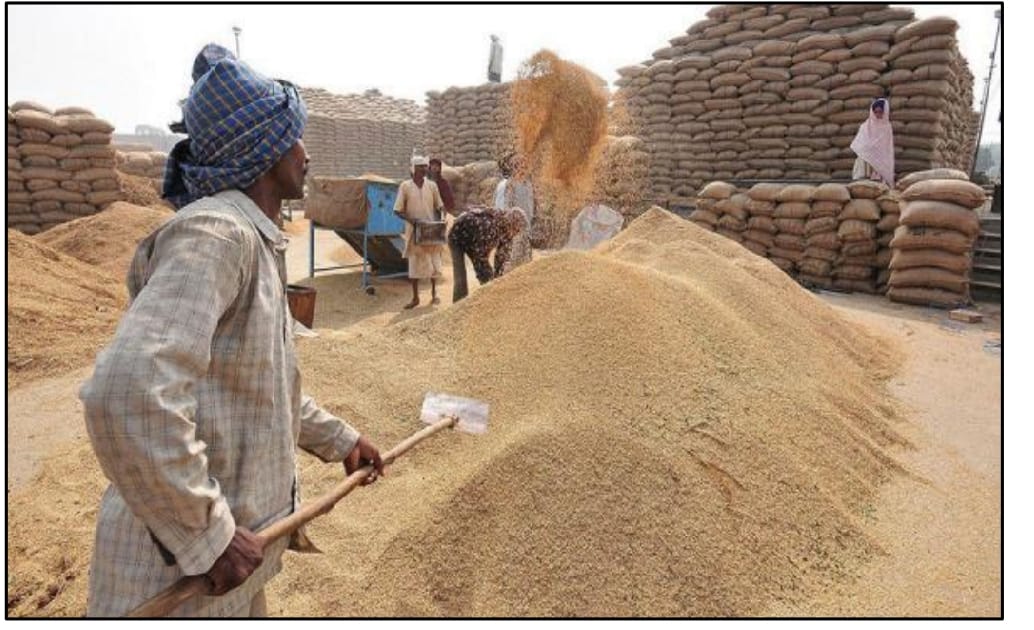

On the ground, this inefficiency is visible everywhere.

Farmers are forced to sell immediately after harvest because storage simply does not exist. Produce is handled without cooling, packed without standards and transported without temperature control. Post harvest losses in fruits and vegetables routinely reach thirty to forty percent. That is value cultivated and then destroyed.

Water inefficiency is even more serious. Pakistan produces roughly 0.6 kilograms of crop output per cubic meter of water. India produces roughly three times that amount. Countries such as Jordan have achieved even higher productivity despite harsher natural conditions. The gap is not about farmer competence. It is about incentives. Water is underpriced. Inputs are subsidized. Outcomes are rarely measured.

We reward volume. We do not reward efficiency.

Why nothing changes

Inefficiency has beneficiaries.

Importers profit from what we fail to process. Traders profit from distress sales. Subsidy regimes reward acreage instead of yield. Politically connected actors capture cheap credit and underpriced water. Meanwhile, investors willing to build storage or processing plants are asked to finance projects at rates that make payback unrealistic.

An efficient system threatens bargaining power. It reduces discretion. It introduces transparency.

That is why reform rarely fails loudly. It fails quietly through delay, indifference and procedural exhaustion. Organized capture at chokepoints has always proven stronger than reform architecture.

If reform is to succeed, it has to work around those chokepoints rather than attempt to negotiate with them.

Three moves that can actually change outcomes

First, concessional financing for real assets.

Each province should establish an Agriculture Infrastructure Fund offering fixed rate financing in the six to eight percent range for seven to ten years. The focus must be strict. Cold storage, aggregation hubs, food processing and modern irrigation systems.

Agriculture is constitutionally a provincial subject, so execution must sit there. But federal guarantees and performance benchmarks can strengthen provincial accountability. Geographic clustering is critical. Punjab’s citrus belt, Sindh’s mango and banana corridors, KP’s apple regions and Balochistan’s date production areas all need integrated cold chain networks, not isolated projects.

Publish quarterly dashboards showing storage capacity added, jobs created, exports grown and imports substituted. Let provinces compete.

Second, allow used equipment imports.

Pakistan does not produce advanced cold chain systems or modern food processing lines at scale. High duties on certified used equipment only inflate costs and discourage investment.

The real dependency to fear is not importing machinery once. It is importing finished food every year because we refused to import the equipment needed to process our own output.

Third, link incentives strictly to performance.

Offer time bound tax relief only to projects that meet independently verified targets such as export growth, measurable import substitution or service to smallholders. Include automatic clawbacks if targets are missed. Incentives should begin when operations start, not when land is acquired.

Reward performance, not political access.

The digital foundation

Infrastructure cannot deliver results if we do not even know who our farmers are.

The Punjab Kissan Card has shown what becomes possible when farmers are digitally identified and linked to land and transaction records. Subsidies move directly to verified accounts. Ghost beneficiaries disappear. Banks can assess creditworthiness. Farmers trapped in informal lending cycles gain access to formal finance.

It also enables precision agriculture. Soil specific fertilizer recommendations reduce waste. Pest alerts can be targeted. Outcomes can be measured rather than guessed.

Sindh, KP and Balochistan do not yet operate comparable systems at scale. That is not a technological constraint. It is a governance decision.

Within two years, every province should have the majority of its farmers enrolled in digital systems. Within five years, a meaningful share of cultivated land should operate under measurable precision frameworks. Information infrastructure is the cheapest reform and it enables everything else.

Water is the structural constraint

Pakistan’s water crisis is not only about scarcity. It is about inefficiency.

Significant volumes are lost through seepage before reaching fields. Canal rehabilitation is among the highest return investments available. Drip and sprinkler irrigation should be expanded steadily over the next decade, with support linked to verified water savings rather than blanket subsidies.

Measurement is essential. Without metering and transparent data, overuse and theft continue unchecked. Over time, irrigation pricing must reflect reality, particularly for water intensive crops. Phasing is important, but reform is unavoidable if groundwater depletion continues at current rates.

Fixing what we grow

Infrastructure alone will not help if incentives continue to favor the wrong crops.

Sugarcane remains overexpanded because finance and water are mispriced. Cotton yields have deteriorated. At the same time, Pakistan imports billions of dollars in edible oils and pulses.

Over the next decade, crop incentives must gradually shift. Reduce excessive sugarcane area. Restore cotton through certified seed systems and better pest management. Scale oilseeds and pulses that substitute imports and use less water. Expand high value horticulture for export.

Farmers respond to incentives. If pricing, credit and support mechanisms change, cropping patterns will change.

The political economy reality

This agenda will face resistance. Sugar mills and import lobbies will defend their positions. Fertilizer dealers benefit from subsidy distortions. Politicians often prefer discretionary systems to rule based transfers.

The answer is not abstract debate. It is speed and visible results. Create new winners quickly. Cotton farmers receiving yield linked support become a constituency. Oilseed processors accessing concessional financing become a constituency. Logistics firms benefiting from infrastructure investment become a constituency.

Once farmers experience direct transfers, access to credit and measurable productivity gains, rolling reforms back becomes politically expensive.

Provincial competition can reinforce this dynamic. No chief minister wants to be publicly seen falling behind peers on jobs, exports or farmer enrollment.

The real choice

Every year of delay locks in over a billion dollars in avoidable waste and several billion more in preventable imports.

The transformation required is not complicated in theory. It rests on three pillars. Physical infrastructure such as storage, processing and logistics. Financial infrastructure such as concessional funds and performance linked credit. Information infrastructure through digital farmer identity and precision agriculture.

The third is the fastest and cheapest to deploy, and it makes the other two possible.

If even one province executes seriously, the pressure on the others becomes structural. If all move together, Pakistan can improve its external balance by five to eight billion dollars annually and create hundreds of thousands of jobs.

The question is not whether this is technically possible.

It is whether we continue managing organized inefficiency, or finally decide to dismantle it.

Fazeel Asif

The author is a ex – senior advisor to the Pubnjab government.

He can be reached out at :