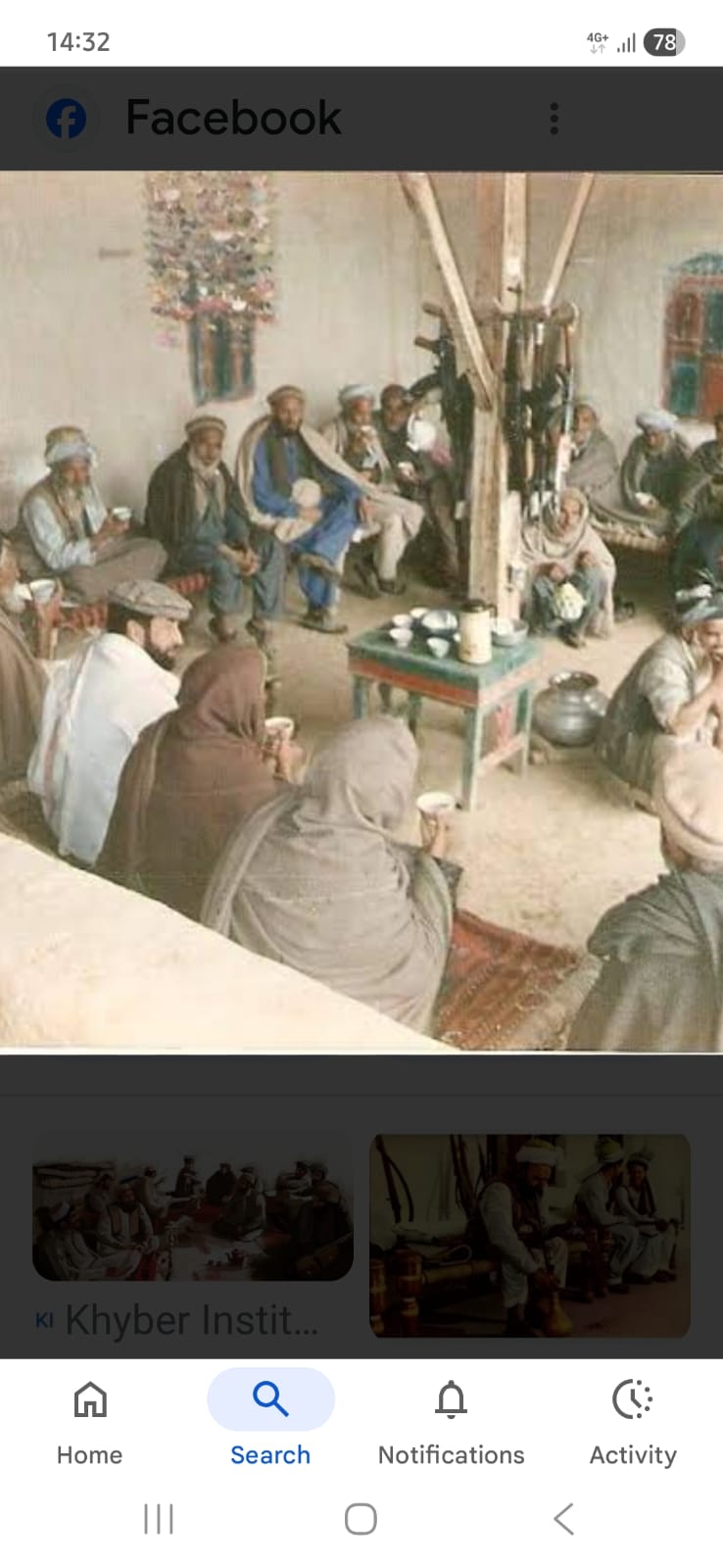

Recently, I was back in my hometown Takht Bhai, sitting in my friend’s hujra — that sacred Pashtun institution where tea is strong, opinions are stronger, and facts are optional. We were armed with a kettle of black tea and thirty years of unfinished arguments.

Within ten minutes, we had done what Pashtuns do best: solved cricket, redesigned the Constitution, and diagnosed the “real problem of the Pashtuns.” Because in our part of the world, every second man is either a political analyst or at least the unpaid strategic advisor to the United Nations. Some even specialise in both, free of cost.

My friend leaned back with the confidence of a man who had just unlocked history’s secret. He quoted a local poet who had apparently discovered the root of all Pashtun suffering. The reason, he declared, that both national and international establishments target us is simple: we possess national consciousness.

I nodded respectfully, the way one nods when a friend claims to have inside information from “reliable sources.”

His evidence?

“We don’t vote for the same party twice.”

I almost stood up and clapped.

If changing political parties every election is national consciousness, then political instability must be a sign of genius. By that standard, confusion becomes wisdom, impatience becomes ideology, and every disappointed voter is a revolutionary thinker. Perhaps we should publish a handbook: How to Achieve National Consciousness in Five Easy Party Switches.

But as the laughter settled and the tea grew cold, his argument refused to leave my mind. Was this really consciousness? Or was it simply frustration wearing patriotic clothes? Is true national awareness measured by how quickly we abandon one banner for another — or by how patiently we build institutions that outlive banners altogether?

In the hujra, answers are always immediate. In real life, they are not.

And that is where the discomfort began.

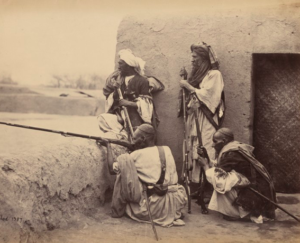

I kept thinking: if Pashtuns are as conscious as we claim, how is it that throughout recorded history they have so often been exploited — from the era of the Mughal Empire to the rule of the Sikh Empire, from the British Raj to the present day?

A truly conscious nation does not drift helplessly through centuries of manipulation. It reads power, anticipates strategy, and negotiates from strength. It protects its interests with foresight, not just fury. If we were as strategically aware as we insist, would we repeatedly find ourselves reacting to events rather than shaping them?

History is not kind to those who mistake emotion for strategy. A conscious nation does not merely resist exploitation; it positions itself so skillfully that others must reckon with its interests. It builds institutions, alliances, and economic strength. It learns from defeat. It adjusts.

Bravery alone cannot prevent exploitation. Pride alone cannot secure autonomy. Without organization, unity, and long-term planning, even the fiercest people can be outmaneuvered.

So the uncomfortable question remains: have we been conscious — or simply courageous? Because the two are not the same.

Professor Shehryar Khan, a scholar of international relations and Pashtun history, made an uncomfortable observation. He said Pashtuns suffer from self-praise. We have built such a powerful narrative about ourselves that we no longer allow the possibility of error.

We are brave. We are honorable. We are loyal. We are fearless. Under the sun, we claim all virtues. Mistakes? Those belong to others. If we lag behind, it is conspiracy. If institutions fail, it is injustice. If leadership collapses, it is betrayal.

The Professor compared us to the flower Narcissus — the daffodil that gazes into water, falls in love with its own reflection, and forgets the world around it. It is a beautiful metaphor. But also a warning.

Self-respect builds character. Self-worship builds illusions.

He went further. He said Pashtuns suffer from collective amnesia. We forget our own patterns. We romanticize bravery but neglect planning. We celebrate resistance but distrust institution-building. We admire heroes yet remain suspicious of systems.

He said the way Pashtuns treat their women reveals more about their character than any slogan ever could. You can measure a nation’s maturity not by how loudly it speaks of honour, but by how fairly it shares dignity at home.

Tell me, in the entire history of humanity, which nation has truly progressed while keeping its women on the margins? Which society rose to lasting strength by silencing half its population?

He said the way Pashtuns treat their women reveals more about their character than any speech about honour ever could. A nation’s true face is not seen in its slogans, but in the everyday dignity it grants its mothers and daughters.

If you treat women inhumanely — the very women who raise your children — what kind of generation do you expect them to nurture? How can children grow into educated, confident, and modern citizens if they are raised in homes where dignity is denied and opportunity is restricted?

A society that weakens its women weakens its own future. A society that empowers them strengthens the foundation on which every lasting nation is built.

Centuries before modern analysts, the warrior-philosopher poet Khushal Khan Khattak — Khushal Baba — had already diagnosed this condition.

In one of his poems, after travelling through Tirah and reaching Swat, he describes meeting the so-called nobles of his people. The improved rendering of his lines would read something like this:

“I crossed the valleys of Tirah and arrived in Swat.

I met the high-born among the Pashtuns.

I searched their faces for wisdom and true courage —

I found neither.

And I returned, my heart burdened.”

This is not an enemy speaking. This is a son disappointed in his own house.

In another place, Khushal Baba is sharper, almost impatient:

“They possess neither learning nor insight.

They are lovers of quarrel and division.

Advise them all you wish —

They heed neither elder nor teacher.”

Notice the pain behind the words. He is not mocking his people; he is grieving for their wasted potential. He understood something timeless: bravery without wisdom becomes noise. Pride without self-correction becomes decay.

Today, we proudly repeat that Pashtuns are fearless. History supports that. But fearlessness alone does not build universities, economic systems, policy frameworks or stable institutions. Modern battles are not fought only on mountains; they are fought in classrooms, laboratories, and negotiating tables.

And here is the uncomfortable question: if we are so conscious as a nation, why are we so easily divided as a people? Why do personal egos overpower collective goals? Why do we change political loyalties with passion but rarely change structural weaknesses?

Perhaps our “consciousness” is reactive rather than strategic. We react strongly. We protest loudly. We feel deeply. But do we plan patiently?

There is something almost comic about how quickly we attribute every setback to grand designs against us. The world, we assume, wakes up every morning thinking about how to contain the Pashtuns. It is flattering. But it is also convenient.

Blaming others protects pride. Self-examination threatens it.

Yet this is not a story of condemnation. It is, as the headline says, a love letter — and a warning.

Pashtuns possess extraordinary resilience. Their hospitality is not mythology; it is lived reality. Their poetry carries centuries of dignity. Their sense of honour, despite distortions, still shapes daily conduct. Their courage is not imaginary; it is documented in blood and memory.

But if courage is not matched with critical thinking, it becomes self-destructive. If pride is not balanced with humility, it becomes blindness.

Khushal Baba criticised because he cared. He understood that a nation unwilling to listen to its teachers and elders cannot move forward. Criticism, when rooted in love, is not betrayal — it is responsibility.

Perhaps the real revolution for us is not in changing political parties every election cycle. Perhaps it lies in changing our relationship with ourselves — from admiration to introspection.

The daffodil is beautiful when it blooms. But if it falls too deeply in love with its own reflection, it risks drowning.

A nation, like a mountain, survives not because it praises itself — but because it stands firm, learns from storms, and strengthens its foundations.

The question is simple, and uncomfortable:

Do we want to be admired — or do we want to endure

Zalmay Azad

The author is a senior journalist based in Islamabad